-

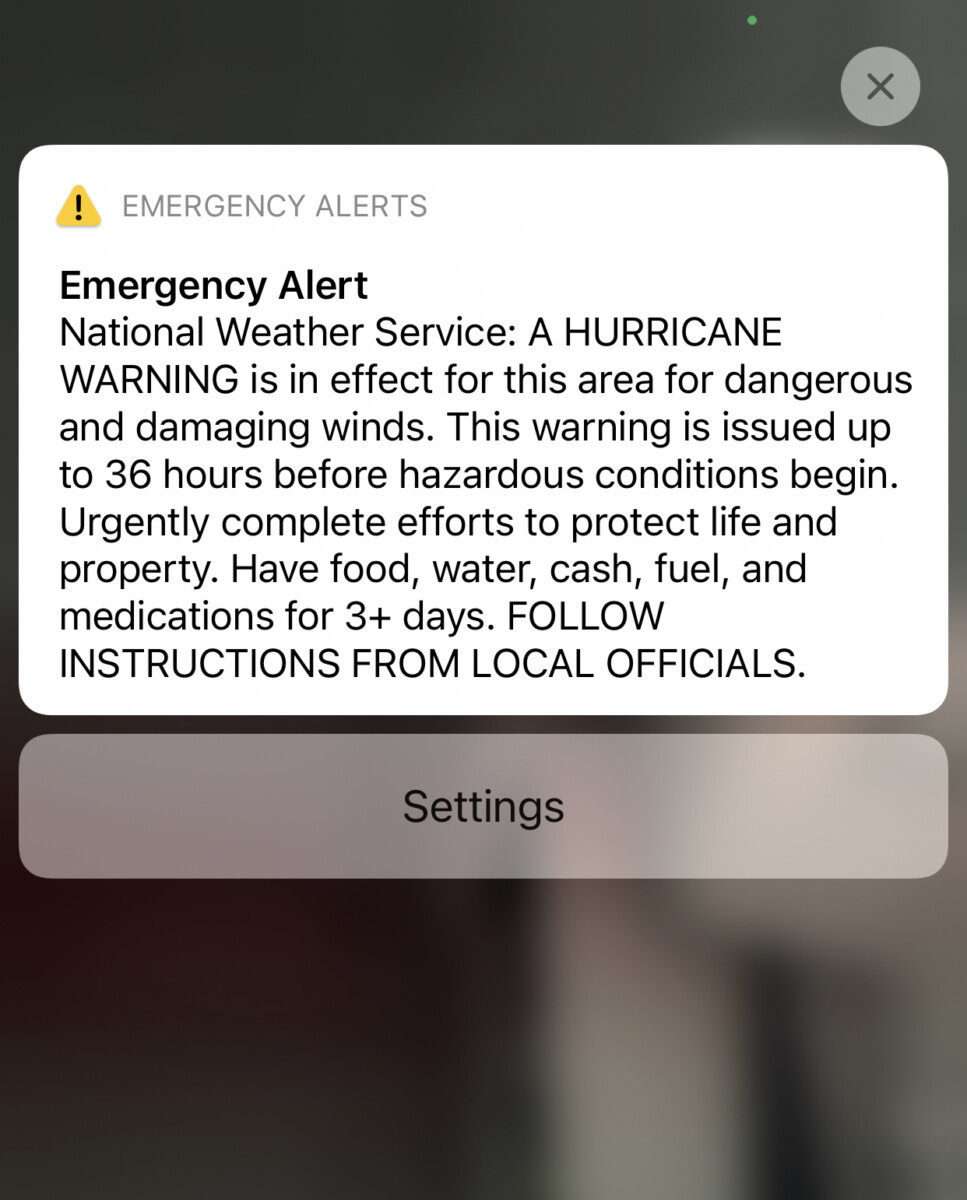

Hurricane Season: Why don’t they just leave?

If you live in the Southeastern United States, during the months of June through November, you can expect to hear a number of reports of “activity” developing in the tropics. Hurricane season is yearly, so those newscasts are expected. Being from the South, you begin to even find interest in learning the storm names chosen…

-

Time to Travel

Outside is open and I wasn’t really prepared A baecation, solocation, familycation, any type of vacation, except a staycation is what I need. The thought of going somewhere just seems so whimsical! No matter what the requirements, mask mandates, no sandals, all plaid only, I am willing to abide by them. I can.not.take.this.anymore. It’s time…

-

The Etiquette No One Taught You

Three things your mother should have told you about. Sometimes, tough love is exactly what you need. Sometimes, it takes a friend (or a stranger) to tell you what your parents should have taught you. Sometimes, someone just has to say the thing you’re not supposed to say. Well, today is your lucky day! I’m…